[English version at the end]

Los mitos de barbarroja (VIII)

Moscú era indudablemente en 1941 (y es hoy, igualmente) el centro de primer orden político, industrial, social y de comunicaciones en la extinta URSS. La caída de Moscú, si bien hubiera podido suponer un duro golpe moral, no hubiera tenido sin embargo una repercusión decisiva para la derrota final del RKKA o para provocar el derrocamiento del régimen de Stalin. De hecho durante el otoño de 1941, cuando las tropas del mariscal de campo Fedor von Bock se aproximaban amenazantes a Moscú (Operación «Tifón»), el gobierno comunista se trasladó a Kuibyshev (Stalin permaneció en Moscú por motivos patrióticos). No sólo los resortes del poder trasladaron su sede, sino que también la industria se estaba reubicando ya desde julio a marchas forzadas más allá de los Urales, desde las regiones occidentales de la URSS. Y el Acuerdo de Préstamo y Arriendo (Lend-Lease act) con los Estados Unidos de América entró en vigor, lo que se tradujo en una afluencia de miles de toneladas de valiosos suministros que empezaron a arribar principalmente por vía marítima a la URSS.

Adolf Hitler siempre temió entrar en una fase inconclusa en el desarrollo del combate, una especie de “pantano de la guerra” que el mismo general Erich Marcks (el encargado del planeamiento de la campaña) contempló, en el sentido de que si no se derrotaba al RKKA en el oeste de la Unión Soviética, podría alargarse la lucha indefinidamente desde bases en Asia y Siberia. Esto había que evitarlo a cualquier coste y la estrategia del Heer no podía ser otra que mantener su maquinaria militar en movimiento constante, asestando golpe tras golpe en espectaculares batallas de cerco. El punto de ruptura del RKKA se alcanzaría tarde o temprano al encajar un número determinado de derrotas catastróficas. Por lo tanto poseer las capitales de la «Madre Rusia» era desde luego deseable, pero no determinante. La URSS era sencillamente demasiado grande. No olvidemos los objetivos geográficos de “Barbarroja”: Alcanzar la línea territorial, de sur a norte Astracán-Volga-Arcángel.

Gran parte del generalato alemán, incluído el jefe del estado mayor del OKH, Franz Halder, consideraba Moscú el objetivo natural que automáticamente les daría el triunfo. Esto fue, incluso antes del mismo inicio de la campaña en el este, fuente de agrias discusiones con el Führer. Uno de los principales defensores de esta estrategia fue Heinz Guderian. No obstante, de haber caído Moscú aún tendría Stalin vastos recursos que movilizar desde otras regiones más remotas. Por añadidura y sobre el impacto psicológico que hubiera supuesto sobre el Ejército Rojo de Trabajadores y Campesinos y el pueblo soviético, la pérdida de su capital no hubiera sido tan desmoralizador como para cesar la resistencia. Y esto ya aconteció. La historia probó en 1812 que la captura por Napoleón y la famosa quema de Moscú, volvieron más orgulloso y resistente al pueblo ruso que rechazó cualquier capitulación. Esto debe explicarse entre otros factores por el tradicional apego de este pueblo a su tierra unido a ella por un arraigo milenario. Y había otros numerosos enclaves “sagrados” que podían reemplazar a la ciudad de la Plaza Roja como símbolo para continuar la lucha.

Adolf Hitler nunca compartió acertadamente la opinión «pro-Moscú» de sus generales. En agosto de 1941 se produjo un parón operacional en todo el frente del este. La idea del Führer era distraer los Panzergruppen del Grupo de Ejércitos Centro hacia el sur y norte con el doble objetivo de sellar Kiev en una maniobra de cerco sin precedentes y capturar Leningrado, cuna del bochevismo, y enlazar con sus aliados finlandeses. Al desposeer al Grupo de Ejércitos Centro de las cuñas Panzer de Hoth y Guderian automáticamente cedía la iniciativa al Zapadnyj Front o Frente Occidental del Ejército Rojo pero esto no fue entendido por muchos comandantes sobre el terreno. Guderian volo ipso-facto al cuartel general del Führer en Rastenburg, la famosa «Guarida del Lobo», para intentar que Hitler desistiera de esta estrategia que dejaba Moscú relegado a un segundo plano. Es cuando el caudillo alemán acusó a sus generales de no entender los aspectos económicos de las guerras, pues la bolsa de Kiev ofrecería al Reich las riquezas mineras y agrícolas de Ucrania. Finalmente en una encendida discusión con el jefe de tropas acorazadas Adolf Hitler accedió a que el Grupo de Ejércitos Centro continuara en dirección a Moscú, pero de momento sólo con la infantería. Moscú definitivamente tendría que esperar.

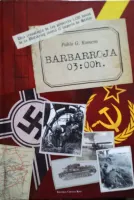

¡Ya a la venta Barbarroja 03:00 hrs!

¿Te ha resultado de interés este artículo? ¿Querrías conocer los detalles de esta y las demás operaciones?

¡Adquiere la obra cronológica Barbarroja 03:00h en edición de coleccionista!

Deja tu comentario abajo y sigue CONQUISTAR RUSIA punteando en la opción «SEGUIR / FOLLOW» a la izquierda de la página

[English version]

Myths of Barbarossa

eighth MYTH: moscow, yes or no?

Moscow was (as nowadays is) in 1941 the first political, industrial and communications network of the extinct USSR. The fall of Moscow could have posed a severe moral blow, but would not have had a decisive fact for the final defeat of the RKKA or even to provoke the collapse of Stalin’s regime. As a matter of fact during the Autumn of 1941 when Generalfeldmarschall Fedor von Bock‘s Army Group Centre was approaching Moscow (Operation «Typhoon»), the Communist government had left to Kuibishev (Stalin stayed behind for patriotic purposes). Not only the brunt of the Soviet power changed its location but also the industrial network was being relocated at full speed from the Western regions of the USSR towards beyond the Urals. And the Lend-Lease act signed with the United States of America started the massive flow of valuable supplies arriving into the USSR through the Arctic Sea.

Even before the commencement of the campaign in the East Adolf Hitler always feared to get into an inconclusive phase of operations; a so-to-speak quagmire or standstill that the same General Erich Marcks (the man in charge of the planning of «Barbarossa») always had in mind, making it absolutely necessary to defeat the RKKA in the Western regions of the USSR. Otherwise the fight could indefinitely be waged from remote bases beyond the Urals or Siberia. This had to be avoided at all costs and the Heer’s strategy could not be other than to keep its military machine in a constant move, dealing harsh blows in spectacular encircling battles. The Red Army‘s breaking point would be met sooner or later after a number of catastrophic defeats. Consequently to seize Mother Russia’s cities was certainly desirable but not determining. The USSR was simply too large. We must keep in mind the territorial objectives pursued by «Barbarossa»: The line Arkhangelsk-River Volga-Astrakhan.

A good number of German generals, men like OKH Chief-of-Staff Franz Halder, considered Moscow the natural objective that would end the campaing. This, even before the commencement of the Eastern campaing, was a source of sour disagreements with the Führer. One another supporter of this strategy was Heinz Guderian. But even if Moscow had been taken Stalin would still have at his own disposal vast resources to mobilize. Additionally and regarding the psychological impact that would have posed on the Red Army of Workers and Peasants and the Soviet people, the loss of their Capital city would not have been as decisive so as to cease all resistance. And this happened already. History proved in 1812 that the capture of Moscow by Napoleon and its famous arson turned the people even more proud and resilient rejecting any humilliating capitulation. This can be explained due to the traditional rooting of the people with their land. And there were many other «sacred enclaves» that could have replaced the capital city as a symbol in order to continue the fight.

Adolf Hitler never shared the pro-Moscow opinion of his generals. In August 1941 occured an operational halt in the whole Eastern Front. Hitler‘s idea was to use both Army Group Centre‘s Panzergruppen towards Leningrad and Kiev. The objective was twofold. With an unprecedented encircling maneouvre to drive south to the east of Kiev and to drive north to support the seize of Leningrad, cradle of Bolshevism, in order to link with his Finnish allies. But by deducting the two armoured wedges from Army Group Centre he automatically yielded the initiative to the Red Army‘s Zapadnyj Front or Western Front. This wasn’t understood by many of his battlefield commanders. Guderian ipso facto flew to Hitler‘s HQ in Rastenburg, the «Wolf’s Lair», to try to make the Führer give up the pursuit of this strategy that rendered Moscow in a lower priority. This is when the German leader regretted his generals did not understand the economic aspects of wars. The fall of Kiev would offer the Third Reich the treasures of Ukraine’s vast agricultural and mining resources. After a tense argument with his Panzer Commander Hitler agreed with great reluctance to allow Army Group Centre to continue towards Moscow, but for the time being just with infantry. Definitely Moscow had to wait…

Did you find this article interesting? Leave your comments below and follow us clicking on «SEGUIR / FOLLOW» at the left of the page

Una respuesta a “¿Moscú, sí o no?”